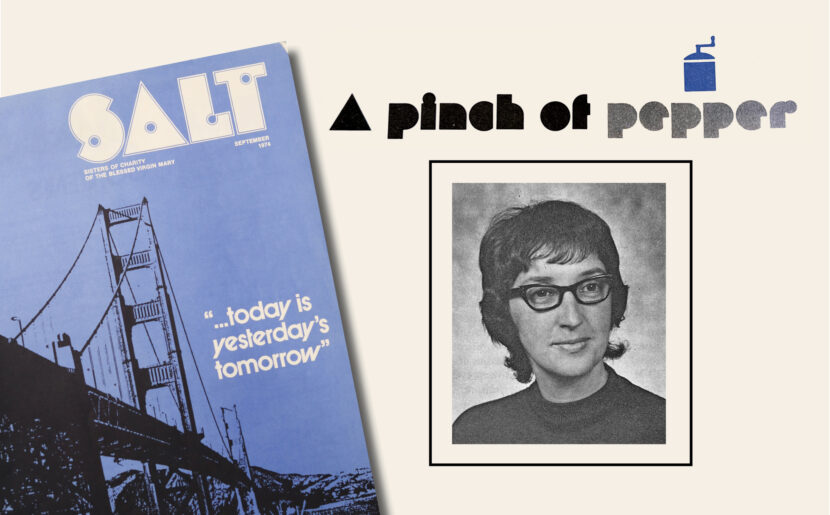

A Pinch of Pepper

by Kathryn Lawlor, BVM

Published in Salt magazine, September, 1974

When the U.S. Supreme Court declared segregation unlawful in 1954, I was teaching in an all-black school in the South one of my students shouted the news to his classmates hey there’s no more segregation a fellow student cynically responded “Oh, yeah? Did you ride the bus to school this morning?” It was a long time after 1954 before Blacks felt free to sit in the front of the bus.

It is with the same cynical spirit that I ask, “What happened to Archbishop Leo C. Byrne’s committee that was to study the rights of women in U.S. society and in the Catholic Church? This was a group called into being after the Bishops’ synod of October 1971. Such cynicism seems justified when, over two years later, I read up on a task force of women religious who “look forward to the opportunity to contribute to the proceedings of this committee.”

A look backward over the long period of silence appears to make Archbishop Byrne’s vigorous support of women’s rights at the 1971 synod his one brief shining moment. At that time he eloquently stated, “Even in the so-called ‘advanced’ countries which subscribe to the principle of equality, women in fact often occupy an inferior position and are subject to exploitation.”

The pastoral letter on Mary by the U.S. bishops seems to hint that the findings of any study on women are already known, “The dignity which Christ’s redemption won for all women was fulfilled uniquely in Mary as the model of all real feminine freedom.” And when they titled their letter BEHOLD YOUR MOTHER the authors clearly described their model of woman.

Before dismissing the committee as a token gesture toward U.S. women, I do think its original procedure is worth considering. It was to begin with the history of women in American society and in the American Catholic Church. Such information would be a great aid in helping women who indulge in self-deprecation or who feel the need to act out someone else’s perception of them.

However, uncovering the history of women will be a difficult task. Official sources did not seem to record the activities of women in the early American church. A diocesan newspaper recently wrote a history of its 75 years of service in the Northwest United States. Having heard many entertaining tales of pioneer sisters who traveled, usually on horseback, through that territory establishing schools and hospitals in log cabins, I was excited about receiving the newspaper’s account. What a disappointment to read nothing about those hardy women pioneers in the fields of healthcare and education! The history turned out to be a chronicle of Irish male missionaries who landed on the shores of the Pacific Northwest.

Probably the most valuable untapped source for the history of women in the American church is the archives of religious congregations of women. Materials there could not only add a freshness and a depth to the work of the early church, but they could also explain why pioneer church women were forced into a role that left them powerless. Mary Frances Clarke clearly summarized the position in which church and society place women religious when she wrote in 1884 to another sister, “Be careful in communicating to Father Brazill what passes between us as it might lead to trouble.”

The archives of congregations contained descriptions of the efforts of early American women to gain an education, to obtain compensation for their services, and to function in their particular fields of competency. They also reveal instances of patronizing that the “good sisters” suffered in a male-oriented world. Until both men and women hear these untold stories of discrimination and injustice hidden in the archives, there can be no understanding of women’s role in the church and women will continue to “occupy an inferior position and (be) subject to exploitation.”

Since Archbishop Byrne’s group apparently has folded its tents and faded into the darkness, could the next meeting of the U.S. Catholic Conference consider a pastoral letter which would contain a historical narrative of the place of women in the church? Could, in the real spirit of subsidiarity, that letter be authored by women and countersigned by the American Bishops?

Sister Kathryn Lawlor is a member of the Social Science faculty at Holy Name Cathedral High School, 750 N. Wabash, Chicago, Illinois 60611.