Archival Clip: The Great Armed Robbery

by Mary A. Healey, BVM

Monday, May 1, 1967, at St. Dorothy Convent in Chicago: As usual the half-dozen early risers went to the 7 a.m. Mass while the others would go at 5 p.m. Four of us went in the door that opened into the convent yard. I went through the yard, walked the length of the church outside because it was such a lovely morning, and sat in a back pew. Another sister also came through the yard and into a side door (it’s a cruciform church) and sat near the side door where I couldn’t see her. We waited and waited. Finally we decided the celebrant, in Chicago for a year of study, had overslept and left by the door to our yard.

We didn’t know that two robbers had entered the sacristy—probably hoping to take the Sunday collection, which wasn’t there. The sisters had counted it Sunday afternoon, and it was in the convent waiting for Father Clements to bank it. The robbers overpowered the altar boy, tied and gagged him, forced the priest at gunpoint to open the safe, which held the sacred vessels but no money, grabbed all the gold cups, tied and gagged the priest too, and hid both of them. They put the vessels in a bag and ran out another door where the other sister could see them.

She didn’t know who they were but they had no business there so she ran after them. When one of them turned and fired the gun at her, she ran the other way back to the convent to call the police. Just as she left, another sister got tired of waiting and headed for the yard door.

I saw her go, then heard the gunshot, and ran after her yelling. On the way I picked up a chair as if I were going to tame lions and dashed ahead.

Meanwhile the lady who ran the corner candy store where she sold coffee and sweet rolls early in the morning heard the gunshot, saw the men running, called the police and described the car they jumped into and which way it went. The police stopped them with their loot within minutes and took them to Gresham police station.

When I ran past the sacristy making so much noise, the priest and altar boy began banging with their feet, so I investigated. I found the boy on the floor of a vestment press and told him, “Wait a minute. There’s somebody else.” The priest was on the stairway to the basement. I untied him and he shot out the door. We never saw him again. Later I learned he went to the rectory, packed all his stuff into his car, told the pastor he was leaving, drove to the university, and shook the dust of St Dorothy’s from his feet. After I released the altar boy, he followed me home into our kitchen where the cook who made our dinner already was putzing around. I asked her to give him something to eat. What else can you do with a boy?

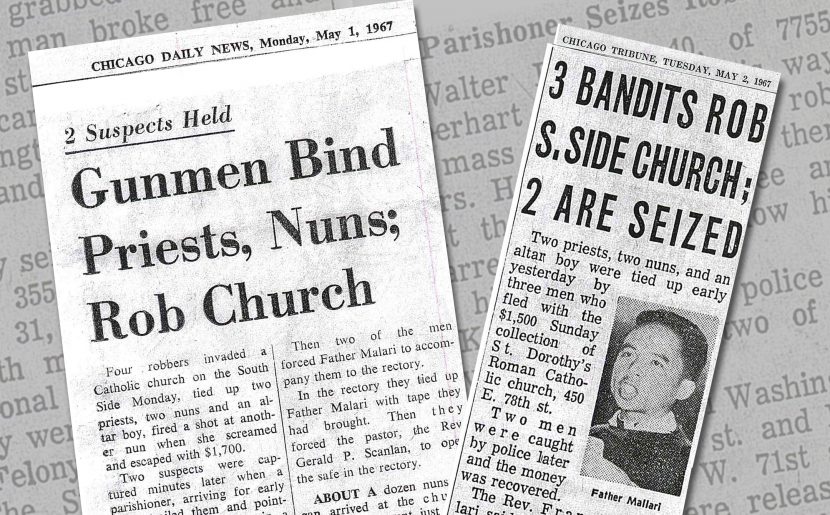

Of course this police news sent reporters to the rectory where Father Clements, who had been in bed during the robbery, was up, dressed, and ready to take charge. He told the reporters not to bother the sisters; he would tell them all about it. He himself hadn’t asked the witnesses, so I guess he relied on infused knowledge and told them what he decided had happened. All four Chicago daily papers had the story wrong in some respect. One said the robbers had rounded up a dozen nuns; I phoned that editor, chewed him out, and told him that when I worked on our school paper in high school, our teacher would not accept such sloppy journalism.

The inaccurate front-page stories didn’t end the matter. The aftermath was on front pages for the next two weeks. The robbers had been booked at the police station and called a lawyer who showed up shortly with release papers signed by a judge in Berwyn. Anyone calculating the distance between Berwyn and the station knew it would be impossible for the lawyer to get the document from the judge in that time. He must have had a document already signed by the judge and filled in the other information. Highly illegal! That investigation led into a bigger one that uncovered a racket and a daily outrage.