Gladly She Would Teach and Gladly She Would Learn

Published in Salt magazine, Summer of 1988

by Kathryn (John Laurian) Lawlor, BVM

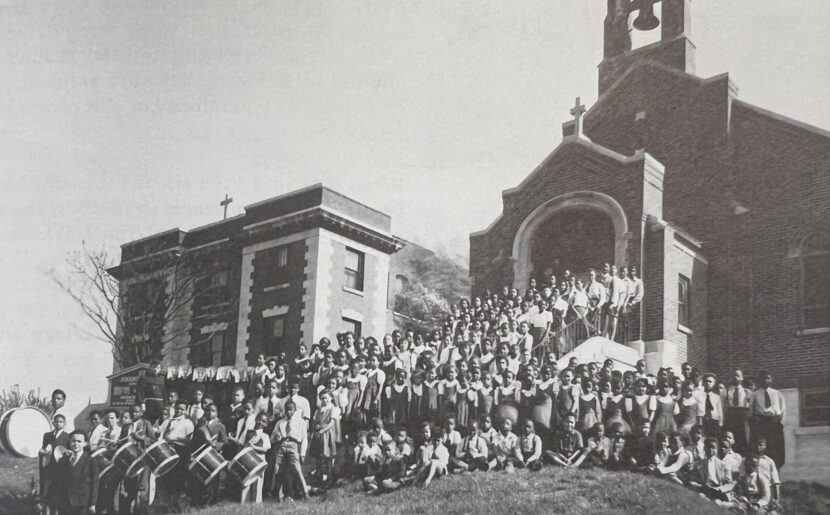

An interview with Kilian Pollard, BVM on the occasion of the 50th Anniversary of St. Augustine, Memphis, Tennessee.

There’s a story in the Congregation that Sister Mary Serena was told not to unpack her trunk when she was sent from the Novitiate to Immaculate Conception Academy because she would be there only a short time. Fifty-five years later she was buried from the Academy. Were you told to unpack when you were sent to Memphis?

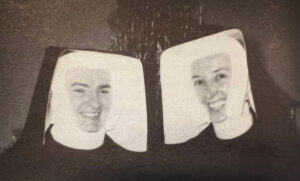

No, no, nothing like that. I had been at St. Odilo’s, Berwyn, [Ill.] for a couple of months, just out of the novitiate, when Richardine [Quirk, BVM] sent me here. Jean Emile [Cofone, BVM] and I came together in August 1952. At the time I was told it would be a couple of years.

During the past 35 years you’ve lived through a powerful piece of history: Vatican II, the Black Movement, the rise of the New South. Let’s begin with the work you did when you arrived.

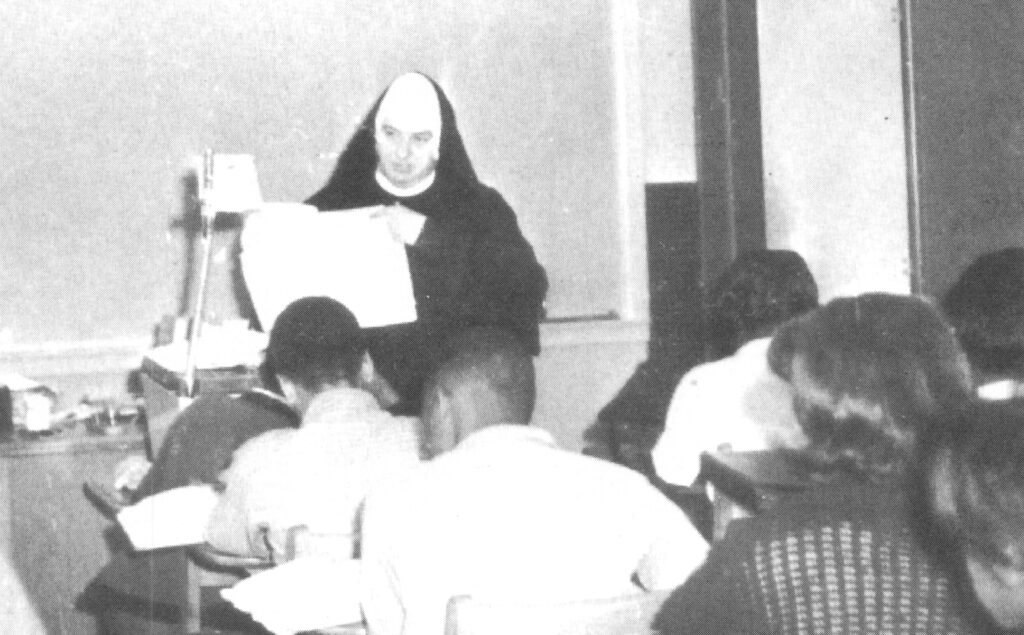

For the first two months I taught 8th grade. Then one day in October, Norberta Becker], you remember how casual she was, came into the community room and asked, “Anyone here know any Spanish?” Of course, I knew enough not to open my mouth. But Francisca [Endovina, BVM], I’ll never forgive her, said, “Kilian knows Spanish.” Norberta asked how much Spanish I had taken. When I said I had a minor in it, Norberta said, “Teach it.” So, the next day, I started teaching Spanish in the high school. Then the next summer I was sent off to Loyola [Chicago] to get a Master’s in Spanish. My major at Clarke had been in history. Later, in the ’60s when I had my own choice, I returned to Loyola and got a master’s in counseling.

Then during most of your years here, you taught Spanish in the high school?

On, no, no. I taught religion, of course. You know in those days every religious could teach religion! Then I taught American history, English and math because I had credits in those subjects. What we taught depended on the credits the other sisters had who were sent here through the years. If they had more credits in a subject then they taught it.

When did St. Augustine’s High School become Father Bertrand?

Nineteen fifty-seven. I opened Father Bertrand as the Senior teacher in 1957, and I closed it as the Senior teacher in 1970. Then it became, and still is, the grade school. Every morning, the pastor from St. Augustine’s drove us to Bertrand in a van we called “The Black Maria.” And if we weren’t ready to come home with him at 3:30 every afternoon, we walked. Many a time I walked back to St. Augustine’s. It took about a half-hour.

Wasn’t St. Augustine’s building condemned, and you had to move out?

St. Augustine’s had been the Edna Mae Oliver Home and Hospital for unwed mothers. We moved from there in 1965 to neighboring St. Thomas Convent. Those were the days of white flight. The white people in the area left for Whitehaven (a south Memphis suburb) and into the new parish and school that had been built for them.

Except for ten or fifteen whites, who have been with us all these years, St. Thomas became the Black parish and grammar school. We really didn’t want to move to St. Thomas.

In the late ’50s we had plans on the drawing board for a parish complex on the Father Bertrand property, the same plans we are trying to build today in the late ’80s. We just got a letter one day from the diocese which said, “You will move to St. Thomas.”

Some of the people from LeMoyne Gardens refused to move into a building left by whites, and they left the Church. What the white Catholic Church cannot understand is the loyalty of the Blacks to their own “church.” They aren’t like white Catholics who go to the nearest church in the neighborhood. Today, we have Blacks living in the suburbs who travel every Sunday to St. Augustine for Mass. They ignore parish boundaries. White neighborhood churches don’t have the music or anything culturally for the Black Catholics.

Recently, one of our parishioners interviewed on TV for the 50th anniversary said he tried going to the Catholic church in his neighborhood for a month.

When he moved into the pew, the white people moved over. When he tried greeting them after Mass, they moved on. After three weeks he said, “I don’t need this. If the whites aren’t going to stay around and greet one another after Mass, they sure aren’t going to stay and greet me.” As you remember, our people love to socialize after Mass.

When you said, “the music,” I remembered during my years at St. Augustine’s in the ’50s, the music was the same as that in Davenport, Iowa. What do you mean by “Black music”?

Well, everyone used Latin in those days. But you know Evangelice [Swift, BVM] had a way with the music. Remember how she played all those Irish songs on the chapel organ as background music while we sang the office? She always had Black songs for Christmas. But it was really after the vernacular, coming with Vatican Il, that Black music came into its own and it’s now a real part of our church.

I recall on the day the Board of Education Vs. Brown decision was announced in the early ’50s, one of your students came into the classroom shouting, “There’s no more segregation,” and someone answered, “O, yeah? Did you ride the bus to school this morning?”

I don’t remember that, but I do remember that Robert Smith won an essay contest sponsored by the National Council of Christians and Jews for Brotherhood week. The group couldn’t give him his award at its dinner because Blacks weren’t allowed in! They came later to the school and gave it to him. Wasn’t that the height of ridiculousness?

Describe how Father Bertrand High eventually became Memphis Catholic?

Nothing was really done about segregation in the Catholic schools until after Martin Luther King’s death. At one time we were the only Catholic high school in the whole state of Tennessee Black children could attend.

Then in the late ’60s a few token Blacks were accepted in some schools, but these were very specially chosen. In the meantime, the diocesan school office decided Father Bertrand should close because it said the enrollment was down. When some other teachers and I protested, the office made a compromise. In 1970 the three high schools that had declining enrollments would be merged into one, which would be called Memphis Catholic.

It was a very difficult time. We were merging an all girls’ school and an all boys’ school with a school of a different culture, into a building that was too small. Parents complicated the problem by telling their children such things as, “Don’t use the school’s bathrooms.” Everything became very touchy, and some things still are. A dance can become a real issue if the band doesn’t provide the right balance of music.

But now, parents are sending their children here because they know they’ll be in a realistic environment, and they will receive a good education. We have Blacks and whites, boys and girls, rich and poor, and about 85 percent of the graduates go on to college.

In recent years, some Blacks told me that in our Black schools we white teachers tried to make little white children out of little Black children. Did you ever receive such a criticism?

No, no one has ever said that to me. Just the opposite. I’ve heard only praise from graduates about their former teachers. However, today I’m very concerned about that. There seems to be a turning away from the Black culture by more affluent Black parents, and they are putting pressure on their children to become more like whites. That’s why I feel there is such a need for Father Bertrand grade school. First, the Black children need to become more aware of their Black identity, their Black culture, their Black history. There is an unfortunate turning away from the “Black is beautiful” theme of the early ’60s by some affluent Blacks.

In the ’50s I can’t remember Black parents wanting their children to learn of their culture. I just remember them wanting their children to get into college.

Right. In the ’50s education was so very important. I remember parents trying to get their children into our crowded classroom. When we said there was no more room, the parent said, “I’ll bring a chair.” And you remember in those days if the children didn’t learn they said, “Beat them.”

I see an award from the Catholic Human Relations Council that has your name on it. How did this happen?

I really don’t know, but I’m sure it’s in recognition of all the BVMs’ work in Memphis. Look closely at the design. Frank Hayden* did it. He also designed the award Black Catholics presented to the Pope when he visited New Orleans last September.

I’d been a member of the council since the middle ’60s to help Blacks gain their rights. We worked to get Black doctors on the staff of St. Joseph’s Hospital. In the late ’60s, Otis Brit, a Father Bertrand football player, was the first Black patient admitted to the Catholic hospital. We were very involved in the garbage strike. Also, we have to contend with John Birch-type Catholics who tried to destroy the council.

CHRC asked me to approach the officials at Christian Brothers High School to ask its band to please stop playing “Dixie” at the football games when its team played Black schools. I explained why the song was offensive to Blacks. The official patted me on the head, told me there was nothing offensive about the song, and sent me off as the naive little nun. At the next game we played Christian Brothers, the band played “Dixie.” I was furious. When I told Jim Lyke, our pastor at the time, he wrote a strong letter to the Christian Brothers and sent a carbon to Bishop Carroll Dozier. Bishop Dozier was a real champion of Black rights. The school band stopped playing “Dixie.”

How were you involved in the city’s Black Movement?

The first march in Memphis was in March 1968, when Martin Luther King came. We closed school for the day and told the students they could march with us teachers if they got permission from home. Many said their mothers wouldn’t let them because there were going to be riots. This was the “I Am A Man” march for the garbage workers on strike.

It was poorly organized, and many mistakes were made. Police, who said they wouldn’t interfere, removed King from the head of the line, and then they fired tear gas at the marchers. All pandemonium broke loose. The women and children were told to go for cover in the temple where the march began. Julia [Acosta, BVM] who was with me, fell, and I lost her. Bang Long, a sophomore at that time, came beside me and told me not to rub my eyes. Of course, I had already done that, so he led me to a pew in the temple and he went off to find Julia.

Suddenly, in the midst of all the bedlam and chaos, I heard a voice booming, “In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Our Father . . .” Sister Carmelette [Kennedy, BVM] was standing in front of the temple leading the rosary! The mothers immediately hushed their children and, because most people there knew the “Our Father,” they joined in.

During this calm, I turned around and through the little window in the back, I saw the police pointing their guns, and then, into this temple filled only with women and children praying, they fired more tear gas. Later, they denied doing this, but I saw them. Because this made everyone so angry, even little five-year olds began picking up sticks and breaking windows. The rioting truly began! Martin Luther King returned the next month because he really wanted to led a successful, peaceful march and that’s when he was shot.

I’ve seen Memphis become a Black town. Real estate agents don’t show whites who may be moving into the area any property in Memphis, but only in the suburbs. Right now we’re trying to keep our neighborhood, Midtown, an integrated one. But outsiders don’t hear of Memphis Catholic or of our integrated grammar schools until they’ve lived in the area several years. When some have discovered it, they have moved into Midtown.

What do you feel has happened to you personally over the years?

I was young when I came here out of the novitiate, and I had no experience with poverty or with prejudice. In 1952, I discovered Black children couldn’t even go into a public library. Can you imagine that?

I have received so much from the people in Memphis. I’ve come to understand what it is to be Black, to be a Catholic and to survive. My life has been more than just a part of the school. I’ve been a part of the parish for 35 years. I feel a real connectedness with the older women of the parish. I have the same goals they do. My thinking is the same as theirs.

Was there ever a time when you wanted to chuck it all and get out?

Never. I may have had some bad days, but never to the point where I wanted to leave. I’ve had a good time; I’ve had a great time. It has all been an experience I’m so grateful for. I feel Catholic education has been so important in our people’s lives. One of my greatest joys is to see what has happened to our graduates over the years. For a tiny, poor school we have had so very many students go on to get doctorates.

And you know we were poor! Coach [Waudell] Porter would go around to the white Catholic schools and collect the food they didn’t use from the government lunch programs. He’d pick up some scraps of meat wherever he could, and Mrs. Jackson cooked up Whatever he found. It was the only meal of the day for many of our students.

Now we have graduates who are leaders in higher education. Some like Frank Hayden, Frank Yates, Donald Weddington, have international reputations. We got extra help for those advanced students because we recognized they had talents beyond us.

We have former students in the Memphis fire department, the police force, in law, medicine, in public office, in public education. Charlotte Marshall is the Mother General of the Oblate Sisters in Baltimore. We don’t have any priests, but we do have graduates who are ministers in other churches.

There is such a bond among all those who were ever a part of St. Augustine. That bond extends to all the sisters who have ever taught here. People came from 32 states to celebrate the 50th anniversary. St. Augustine is such a proud part of their history.

Today, I’m seeing the children and grandchildren of the students I taught, coming to Memphis Catholic.

Do you see anything that still needs to be changed?

Oh, I think the Church. As far as Blacks are concerned the Church hasn’t even touched what it needs to do. It has to address the educational needs of the poor. Catholic schools cannot become schools just for the wealthy. There has been no real outreach to Blacks.

I hear complaints that Black Catholic schools have non-Catholics in them. We forget about all the generations of Blacks the Church ignored.

The attitude of the Church in Memphis is, “Let them follow our white culture.” I’ve heard clergy say that Blacks really want to be white! They still tell stories about how the Irish and Italians came to this country and became models for the way to mix and get along. They are totally ignorant of Black culture, of Black prayer, of Black spirituality.

What do you see as your future in all of this?

To work here until I die. Hopefully, by that time I will have seen the new St. Augustine complex built. I want to be buried in the cemetery next to St. Augustine’s Church.

* Since this interview, Frank Hayden, a Guggenheim Fellow and Art Instructor at Southern University, Baton Rouge, La., died in a tragic accident.

- S. Kathryn Lawlor, BVM, taught with S. Kilian at St. Augustine in the 1950s. Presently she is the Purchasing Agent at Barry University, Miami, Florida.

Related: BVM Kilian Pollard was recently posthumously inducted into the Memphis Catholic Hall of Fame, honoring her lifelong dedication to service, education, and social justice. Read more: https://www.bvmsisters.org/killian-pollard-bvm-a-legacy-honored/

Related: BVM Kilian Pollard was recently posthumously inducted into the Memphis Catholic Hall of Fame, honoring her lifelong dedication to service, education, and social justice. Read more: https://www.bvmsisters.org/killian-pollard-bvm-a-legacy-honored/