Pilgrimage to India

Mary Donahey, BVM rides a rickshaw.

by Mary Donahey, BVM

Published in Salt, Spring 1977

Having spent six weeks in India (thanks in part to a Mundelein College grant from the Lilly Foundation), I will try here to corral a few impressions gained from visiting 11 cities: Bombay, Aurangabad, Ahmedabad, Mt. Abu, Udaipur, Jaipur, Delhi, Agra, Khajuraho, Varanasi, and Calcutta.

From the time I arrived in India on December 17, 1976, I was most impressed with the mature religious tolerance of the people. Oh sure, there is a small Jan Sangh party that would like to convert the secular state into a Hindu state and perhaps has done its part to discredit Indian Muslims, but that appears not to be the predominant philosophy. Instead, what is so moving is the Indian respect for a variety of religious perspectives.

Secondly, I was impressed by the seemingly universal assumption on the part of Hindus that God is manifest in everyone and everything. This is enshrined in the words of spiritual leaders, such as Vivekananda, Ramakrishna’s great disciple. It is expressed in the very gesture of greeting. Here one puts one’s hands together in a prayerful way before one’s chest and bows before you, thereby speaking the belief that the divine in you is being worshipped. Such experiences revivified for me my own religious tradition’s doctrine of divine indwelling.

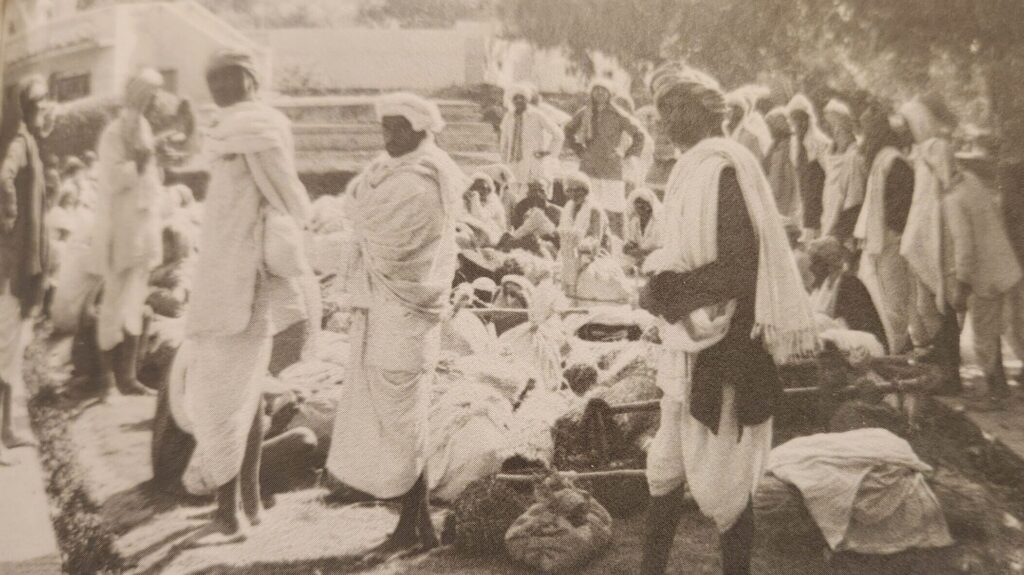

But not only does one experience God in people, one experiences the divinity in many things, including the rising sun and Mother Ganga, as the Ganges River is called. This experience accounts for the teeming multitudes at 6 a.m. on the bathing ghats adjoining the cremations in process along the Ganges at Varanasi. This is a river that has brought to the people in the torrid summer climate cleanliness, which to Ghandi was not next to godliness, but was godliness. As one bathed here, one’s sins were forgiven. That surely had to be sacramentally true on that cold winter morning when I was there. I was there at a most auspicious moment—when the Ganges meets the Jumma River, an event that occurs only every 12 years. Celebrating this feast of Kumbh Mela, January 19, 1977, were millions of pilgrims.

Of course, the divinity is also experienced in the much-touted-in-the-West phenomenon of the sacred cow. Legen has it that the god Krishna, while a child among cowherds, told them to worship not an unseen, abstract god above, but their own cows. It was in the cows where their devotion lay and where God’s blessings to them lay. As they garland their cows, one is reminded of Jesus’s observation, “Where your treasure is there also is your heart,” or Tillich’s recognition that “God is our ultimate concern.” This devotion to a beloved is an expression of the form of yoga known as bhakti.

Thirdly, I was impressed with the attempt of the Catholic missions to respond to the people’s social and liturgical needs. I witnessed this response while staying with the Religious of the Sacred Heart in Bombay, sitting down with the Jesuits in Jaipur to eat buffalo meat and ice cream made from goat’s milk, worshipping at the Vatican embassy’s nunciature in Delhi, roughing it with the priests in Varanasi, and visiting Mother Theresa’s works in Calcutta. Many novitiates are bursting at the seams with entrants from Kerala—a throwback for me to Mount Carmel, 1960.

It was my good fortune to spend some time in Delhi with Sister Jeanette McDermott, a Medical Missionary, who had lived with BVMs in Iowa City. Her work now extends far beyond Holy Family Hospital. In a Delhi slum, we visited a family of 10 whom Jeannette helped to get back financially on their feet. Their only source of income was milk from two buffaloes who occupied half of the family’s small home.

There is, of course, great controversy in India over the state of Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi in the last few years. While I found a B.A. student resenting having to pledge that upon graduation she will convince five people to practice family planning (compulsory sterilization), plant five tree samplings, and teach five illiterates how to read, I also heard sensitive people explain that “there are so many of us” and some of our personal freedoms may need to be temporarily circumscribed in order that the nation may survive.

Although the Emergency is labeled as a socialist revolution from the right, India seems intent upon arriving at zero population growth, planting trees to hold the soil and attract more rain, overcoming illiteracy, encouraging Indian industry instead of imports, and implementing other measures in the 20 point program to overcome corruption progressively. After having found so palatable India’s spiritual fare, of course, I pray that her 20-point program is worthy of her rich, spiritual traditions.

When this article was published, Sister Mary Donahey was on the theology faculty of Mundelein College in Chicago.

Read more historic articles

Read more historic articles

from Salt spanning over 50 years.